Sugar has a long history, dating back thousands of years to the time of King Henry III of England. The sweet craving for sugar has been a part of human evolution, with the phrase “sugar and spice and everything nice” first appearing in a 19th-century poem. Southeast Asia first domesticated sugar around 8000 BCE. The craving for sweetness has always been a part of human evolution, and it became more accessible in the medieval Islamic world around 700 CE.

Sugar-A Bitter History

Before we dive into sugar addiction, it’s important to understand what sugar actually is—and it’s not as simple as you might think. Sugar comes in many forms, from the table sugar you sprinkle on your cereal to the hidden sugars in processed foods. The most common types of sugar we consume are sucrose, glucose, and fructose. Let’s break these down:

- Sucrose is the scientific name for what we typically call table sugar. It’s made of one molecule of glucose and one molecule of fructose. This combination is what you’ll find in most sweeteners.

- Glucose is a simple sugar that our bodies use as a primary energy source. It’s found naturally in many foods, including fruits and vegetables.

- Fructose is another simple sugar, but unlike glucose, it’s processed differently in the body. Fructose is metabolized in the liver and can lead to fat production when consumed in excess. High fructose intake has been linked to conditions like obesity and fatty liver disease.

Sugar-A Bitter History

However, the story of sugar’s rise is bittersweet. Sugarcane plantations spread across the Caribbean and the Americas, becoming the backbone of colonial economies. To meet the growing demand, these plantations relied heavily on the brutal institution of slavery. The transatlantic slave trade and the sugar economy deeply intertwined the horrific conditions millions of Africans endured as slaves on sugar plantations. One powerful example of resistance to this system was the Haitian Revolution of 1791, which established Haiti as the first independent Black republic.

Sugar was once as valuable as gold, but over time, it transitioned from a luxury commodity to a staple ingredient in the Western diet. By the 18th century, sugar fueled economies from the Caribbean to Europe but also fueled brutal exploitation. Sugar plantations generated wealth, making men like Sir William Beckford decadently rich, while enslaved Africans who worked on them endured unimaginable suffering.

In America, sugar’s reach was powerful, with the introduction of the Molasses Act of 1733 imposing a tax on the import of molasses, a crucial component in the production of rum, significantly contributing to the triangular trade among the Americas, Europe, and Africa. Colonists resisted this taxation through widespread smuggling, setting the stage for growing tensions that would eventually contribute to the American Revolution.

The sweetness we crave is not just a modern problem; sugar has a complicated legacy that has shaped nations, driven economies, and led to the exploitation of countless lives.

Addictive or Ancient Appetite?

Sugar addiction is a complex issue that involves various forms of sugar, including sucrose, glucose, and fructose. Various forms of sugar exist, including table sugar typically found in cereals and hidden sugars in processed foods. High fructose corn syrup (HFCS), a sweetener made from corn starch, is one of the biggest culprits for excess sugar consumption. HFCS contributes to about 8% of the total calories in the American diet and has raised concerns about its link to conditions like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Sugar intake doesn’t just come from cake, candy, or sugar added to tea; almost all processed foods in the supermarket contain added sugars. Sodas can have as much as ten teaspoons of sugar per can, and “low-fat” products often compensate for the reduction in fat by adding sugar to maintain flavor. HFCS contributes to about 8% of the total calories in the American diet, raising concerns about the link between it and conditions like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Some scientists argue that HFCS, due to its high fructose content, may lead to greater health risks than sucrose.

From the very beginning of life, humans have had a hardwired desire for sweetness. Our DNA deeply codes an innate preference for sweet tastes in babies from birth. Breast milk, naturally high in sugars and fats essential for growth and brain development, attracts infants due to their innate preference for sweet flavors. This preference stays with us as we grow, shaping how we respond to sweet and fatty foods throughout our lives.

Sugar and the Brain

Our brains run primarily on glucose, a type of sugar that fuels things like memory, learning, and focus. Given that the brain consumes approximately 20% of the body’s energy, it’s natural for us to gravitate toward foods that provide a rapid glucose surge. When our blood sugar drops, the brain urges us to reach for something sweet to replenish its energy. This natural tendency can easily lead to overconsumption in today’s world, where sugary foods are everywhere and designed to be irresistible.

In the mid-1900s, the processed food industry made a pivotal discovery that changed the way we consume sugar and possibly how we have become addicted to it. Researchers discovered that the perfect balance of sugar, salt, and fat created a powerful sensory experience that left consumers feeling satisfied yet craving more. This phenomenon, termed the “bliss point,” allowed the food industry to engineer foods that kept people coming back for more.

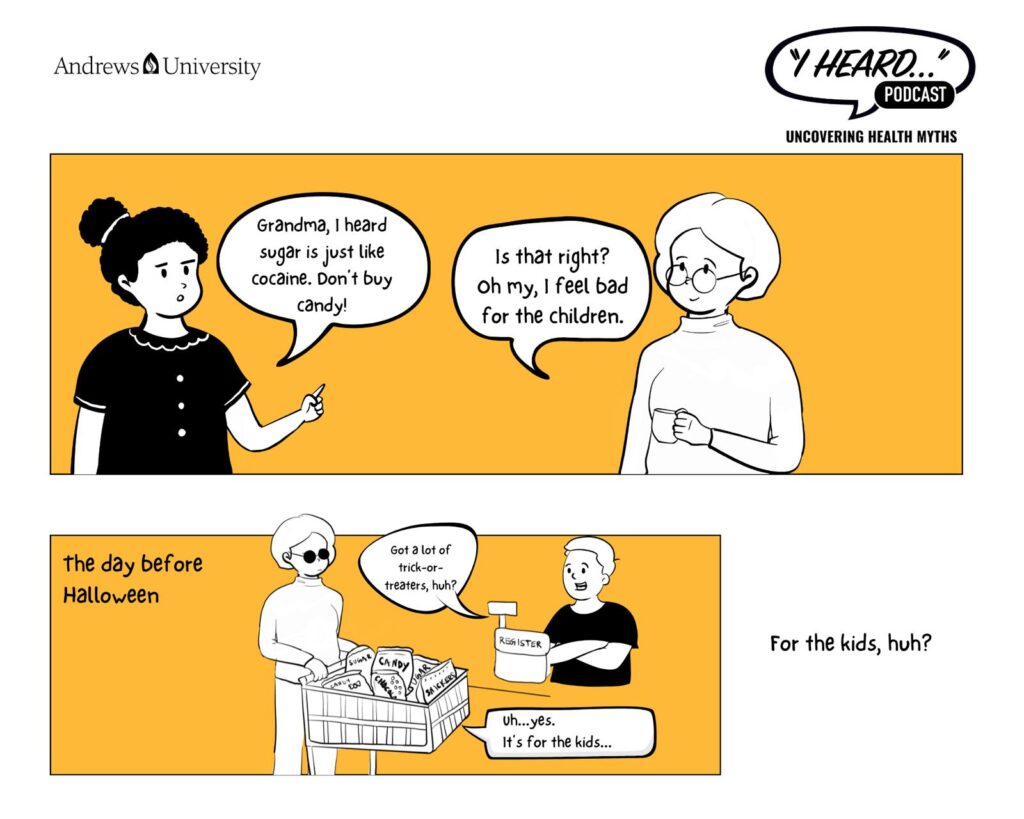

Scientists have discovered striking similarities between the brain’s response to sugar and its reaction to drugs like cocaine. Rats, even those already addicted to cocaine, overwhelmingly chose sugar over cocaine in animal studies. Sugar activates the brain’s reward system by triggering the release of dopamine, the neurotransmitter responsible for pleasure and reward. Drugs such as cocaine activate the same pathway, but unlike drugs, which gradually increase the brain’s response and lead to stronger addiction, the effects of sugar level off, although they can still lead to a form of dependency.

Experts believe that while sugar may be habit-forming, it isn’t as physically addictive as powerful drugs. Once you start using sugar for pleasure or comfort, your brain craves it even when you’re not hungry. Sugary foods provide quick, short-lived satisfaction, making them an effortless fix for emotional relief. But after the sugar high fades, we often experience a crash, leaving us feeling sluggish or moody. This cycle of craving, binging, and crashing mimics the patterns seen in drug users.

In 2014, Australian filmmaker Damon Gameau brought attention to this issue in That Sugar Film, where he consumed around 40 teaspoons of sugar from foods many of us think of as “healthy,” such as low-fat yogurt, granola bars, and juice. The results were shocking: within just three weeks, he experienced mood swings, energy crashes, and weight gain. By the end of the experiment, he had developed early signs of fatty liver disease.

The Global Sugar Battle – Policy and Personal Power

The global sugar battle has seen sugar sneaking into almost everything we eat, and it’s no surprise that our consumption has skyrocketed. Countries like the UK and Mexico have introduced sugar taxes on soft drinks, while Chile leads the charge with bold black warning labels on foods high in sugar. Norway and Canada have even restricted sugary food advertising. In the U.S., many schools have banned sugary drinks, focusing on promoting healthier choices for kids.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has stepped in with clear recommendations: “free sugars,” or added sugars, should make up less than 10% of our daily caloric intake, with an ideal target of reducing it to below 5%. These guidelines are shaping national policies and helping to fuel public health campaigns.

While sugar might not be as addictive as cocaine, it still holds serious sway over our health and habits. It’s time we take charge—both on a personal level and as a society—and reclaim control over what we’re eating.

Leave a Reply